THE FIRST RUPTURES OF BELONGING: On Power, Rank, and the Rise of a Hegemonic Worldview

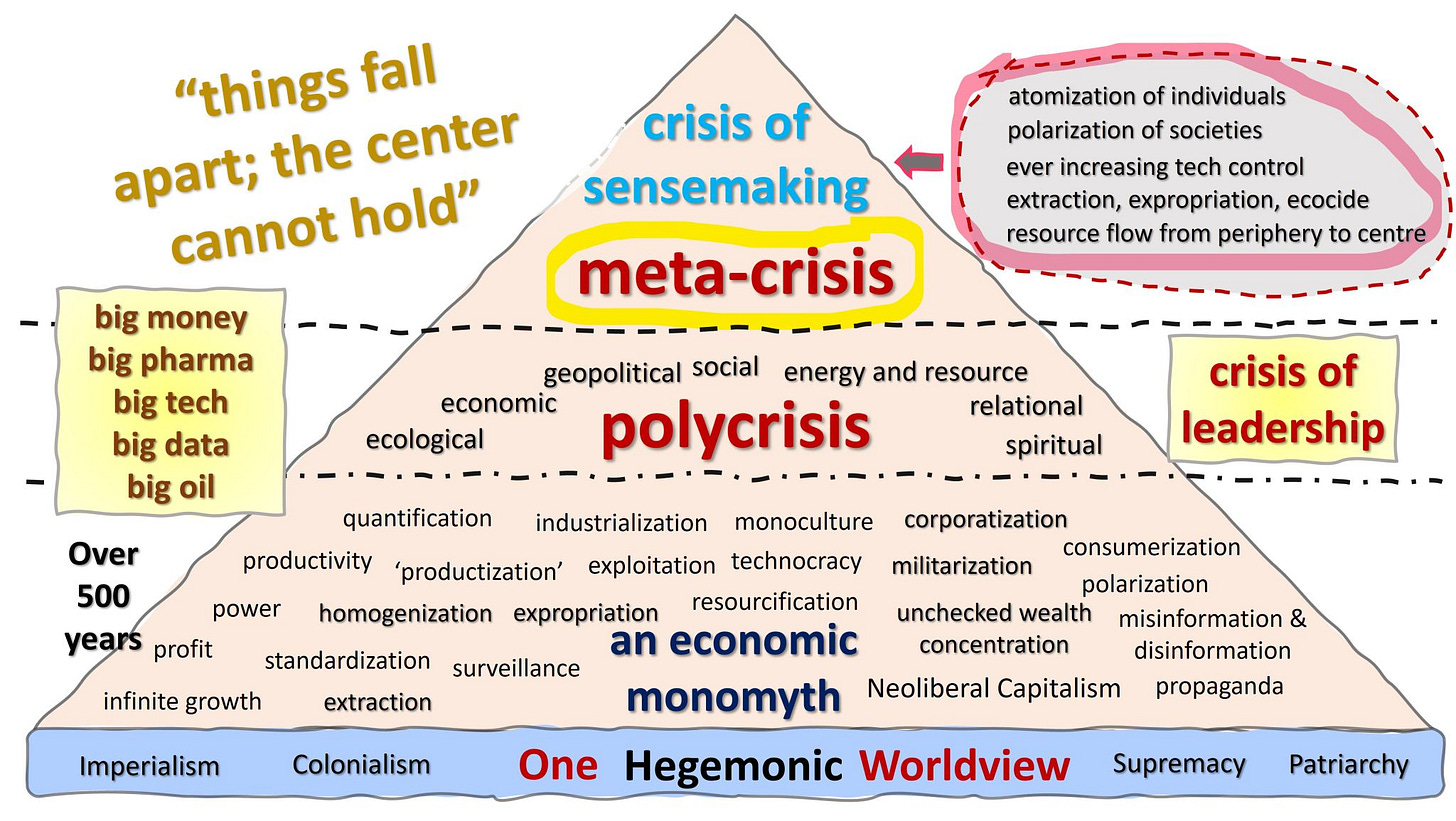

I have been contemplating this image, which a friend and futurist, Sahana Chattopadhyay, shared on LinkedIn.

Last night I had a long and interesting conversation with my husband on what I was exploring around how this “one hegemonic worldview” came from deeply embedded trauma responses that we can trace way back to our evolution as humans. What began as a musing on power and rank as part of natural ecologies turned into something more layered, more ancestral. I began tracing a thread—one that I believe stretches back to our hunter-gatherer days, back to the very first ruptures of belonging.

On Power, Biology, and the Nature of Hierarchy

We, as a species, are genetically wired for hierarchy. We see it all around us in nature - how species survive and interact with each other. This isn’t just a social phenomenon—it’s biological. We see it in the way flocks move, how packs organize, how trees communicate in forests. It’s embedded in the very blueprint of life.

It is also deeply embedded in our genetic make-up. A great example of how hierarchy is embedded at the cellular level is how the egg not only accepts certain sperm but actively rejects or blocks others. The egg does not passively wait for the fastest sperm to arrive. Instead, it actively chooses. It releases chemoattractants that signal to certain sperm and not others. Once one sperm is selected, the egg changes its membrane to prevent others from entering.

At conception, the egg exerts selective power through molecular receptors, binding decisions, and physical changes. The rules of power dynamics—selection, inclusion, exclusion—begin at the cellular membrane.

Power and hierarchy, then, are not inherently oppressive. They are part of a living system’s way of navigating complexity. If even the egg knows how to choose—who to welcome, who to ward off—then selection, rank, and power are not inventions of empire. They are echoes from the beginning of our existence. What matters is not whether hierarchy exists, but how we relate to it, how we use it, and whether we see it as a means to co-steward or control.

I love how Ted Rau describes power in his piece “Power isn’t what we think it is “ as a “potential in the system”.

We can think of power as potential in the system, like a special folding toy that can move this way but not that way. Each configuration has a certain wiggle room or leeway - configurations into which we can bend the system more easily than others…If we see power as potential in a relational and configurational (sub)context, then actor and impact are within the same field. They are and were never separate. We cannot even distinguish between “power” and responsibility. Power is the potential to twist the relational field into a new situation, so responsibility is not an add-on, but intrinsic to the act of twisting. There is no action without impact.

This reframe allows us to see power as movement, as potential, as relational.

Yet there are more areas to unpack when we think of how society came to be and why we are swimming in this cesspool of imperialism, colonialism, supremacy, and patriarchy - a society driven by one hegemonic worldview that Sahana brilliantly wrote about.

On Social Dominance, Eco-Evolution, and Genetic Memory

So how did we get here?

Bruce Lahn in the research on “Social dominance hierarchy: toward a genetic and evolutionary understanding” emphasized the work of Wang et al. on the comparative-genomic and functional exploration, which revealed that dominance hierarchies in social animals have genetic and evolutionary mechanisms underpinning them. These genomic studies on social animals reveal what many of our elders already knew—dominance isn’t just performative, it’s somatic. It lives in our DNA, encoded through time as a means to stabilize the collective and secure survival. This evolutionary scaffolding is not limited to humans—it shapes how ants organize, how wolves lead, how birds migrate.

Studies on eco-evolutionary processes by Mary Burak et al. on Eco-Evolutionary Dynamics: The Predator-Prey Adaptive Play and the Ecological Theater highlight that species‑level adaptations and interactions shape communities in hierarchies. In predator‑prey systems, feedback loops translate environmental stress into structural order and power gradients across species lines.

Eco-evolutionary processes (hereafter, “eco-evo”) occur via reciprocal interactions between ecological and evolutionary processes which enable organisms to both shape and adapt to their environment [8,9]. Ecological processes, such as species interactions and environmental changes, can influence evolutionary change by altering natural selection. This, in turn, can alter the genetic frequency underlying phenotypic traits. These evolutionary trait changes could further alter ecological dynamics, including the nature and strength of species interactions with their environment, competitors, and predators — thereby instigating a new round of evolutionary change and ultimately resulting in an eco-evo feedback loop [10,11]. Eco-evo studies have extensively reported how ecology influences evolution (“eco to evo”), while newer studies investigate the reverse process (“evo to eco”) [4,12,13]. Few studies have examined a complete feedback loop (but see [14]) [8,9,11,15].

Another interesting field of study is the Social Rank Theory. It demonstrates that rank systems—agonistic or affiliative—evolved over 300 million years and are encoded in genomes. The theory suggests that these hierarchical structures and the motivations to achieve and maintain a higher rank are rooted in evolutionary pressures related to survival and reproduction (competing for resources such as food, territory, and sexual partners). They help reduce intra-group aggression, stabilize groups, and allocate resources more efficiently—all foundational to social structures across species.

Social rank can be conceptualized as a function of several related factors, including resource inequity, maintenance and stability of the hierarchy, subordinate coping strategies, mating style, personality variability, and culture (Sapolsky, 2004, 2005).

Recent advances in imaging have enabled the study of social rank in connection with brain structure and function. These studies suggest that the perception of rank is tied to specific brain structures, meaning hierarchy isn’t just learned; it’s embodied. These new findings show that hierarchy is not only cultural —it is encoded and adaptive.

As tribes grew and evolved, structural hierarchy emerged to optimize survival. These hierarchies enhanced adaptability and performance, emerging from structural constraints and survival pressures, not just social behavior. At every level of society, even at the cellular scale (remember the egg and the sperm?), hierarchies form by selective inclusion and protective exclusion.

But how did we evolve to the society that we are in now?

What fractured our sense of collective identity?

What happened between those ancient configurations and the systems we find ourselves in now—systems built on hyperindividualism, extraction, and conquest?

What caused the ruptures that have deeply encoded this hyperindividualism? disconnection to self, others, and nature? control and power over imbalances? assertion of one’s dominance alongside one’s point of view, practices, and prejudices?

Why are we swimming in colonialism, supremacy, and domination disguised as progress?

I returned to a theory I’ve been slowly unwinding: that our earliest evolutionary ruptures—rooted in displacement, exile, and the scarcity of resources—embedded trauma responses into the core of how we relate to power, each other, and the land.

I had a conversation with ChatGPT regarding these musings, sharing my thoughts on how the hunter-gatherer experiences have embedded these survival responses into our genetic make-up. These trauma patterns evolved and adapted as the tribe grew, where scarcity in resources occurred, and changes in interpersonal relationships created discord within the community.

To illustrate this ancestral fracture, here is the story that emerged in collaboration with ChatGPT—a tale not bound to a single tribe, but echoing the archetypes of exodus and exile etched into our collective nervous system.

“The First Rupture” – A Story of Exiles and Nomads

Long before empires and borders, before coins and clocks, we were gatherers of berries, hunters of rhythm, keepers of firelight. We belonged to each other. Until the land whispered limits.

Scene 1: The Withering Grove

The air was drier than usual. The berries that once colored the earth like constellations on the ground had thinned out. The animals had moved upstream, beyond the ridge. The elders of the tribe stood in council. There were too many mouths, too few meals.

It was decided: some would have to leave to find new grounds.

The leaving was not celebrated. It was a severing.

Among those chosen to depart was Aki, a young mother with a baby bound to her chest, her brother, who still carried the memory of laughter in his step, and a few others who bore the weight of leaving with quiet grief. The tribe gave them a goodbye fire, not as farewell—but as prayer. A hope they would return.

They never did.

Scene 2: The Nomad’s Terrain

As Aki’s group wandered through unfamiliar forests and across unfamiliar waters, their senses sharpened. Every rustle became a potential threat. Every shadow is a question mark. They wrapped their fear in silence and called it focus.

Days turned into cycles. The landscape changed. The stories they once told around the fire grew fewer. They had to move quickly, quietly.

When they encountered another group—one that painted their faces differently, carried weapons of bone and bark—they were not met with welcome. There was fear in both camps. Fear that bloomed into suspicion. Suspicion that calcified into aggression.

That night, under the howl of moons, Aki wept not from hunger but from disorientation. She was no longer of a tribe. She was of survival.

Scene 3: The Outcast's Solitude

Elsewhere, in the original tribe, disagreements had grown. One of the younger hunters questioned the elders’ decisions. He was called disrespectful, too bold, dangerous to harmony. Eventually, he was exiled—not with ceremony, but with silence.

He left carrying shame like a second skin.

In the wilderness, he learned to fend for himself. But he also learned to distrust others. He built tools faster, hunted alone, learned to read the skies. He survived, yes—but something in him stiffened. He began to believe that belonging was weakness. That, depending on others, was what got him exiled in the first place.

And when he found others like him—also outcasted, also hardened—they formed a new group. Not around kinship, but around competence. Not around care, but around control.

Scene 4: From Survival to Structure

Over generations, these splintered communities grew. Their stories changed. “Strength” became valorized. “Independence” became holy. “Efficiency” was praised, and “emotions” were buried with the bones of those too slow to survive.

Children were taught that safety came from control.

Leaders rose not from trust, but from dominance.

The wisdom of weaving, gathering, singing together—those rituals of kapwa, of shared humanity—became relics of a forgotten time.

And so it was: a culture birthed from rupture, a structure built from the scaffolding of unprocessed pain. What once were trauma responses became societal rules. Personal protection became policy. And those who did not conform to this new order—to this hegemonic, extractive, patriarchal worldview—were cast again as outsiders.

The cycle of exile continued.

Scene 5: Remembering

But across time and terrain, there were still keepers of the old songs. Grandmothers who hummed lullabies into the bones of children. Dancers who painted circles into the dirt. Herbalists who remembered the scent of community.

They knew.

That healing would not come from power, but from returning.

Returning to each other.

Returning to wholeness.

Returning to the parts exiled in ourselves.

Where Do We Go From Here?

My head is spinning with questions and possibilities. I am intrigued and curious to explore how resource allocation and accessibility, eco-evolutionary dynamics, and cultural scripts around scarcity and survival have all worked hand-in-hand to birth this world of disconnection.

But perhaps, more importantly, I am wondering: what do we need to remember to break the spell?

I would love to invite you to this process of reflecting and remembering.

PAGMUMUNI-MUNI: Think about these…

What parts of myself have been shaped by survival, not belonging?

Where do I still carry the exile in my body, in my relationships, in how I lead or parent?

How does reclaiming ancestral ways of being—like kapwa—help us reorient toward shared humanity in a world designed for separation?

From the selective intelligence of the egg to the eco-evolutionary scripts of survival, we are woven into patterns of power that stretch beyond behavior into biology, history, and culture. Somewhere along this lineage, the sacred web of kinship was torn, and what emerged was not just adaptation, but armoring.

Now, the work is not to discard power or hierarchy, but to return to the wisdom of wholeness. To drop the armoring and return to power that carries potential and protection. To a hierarchy that supports communal flourishing. To systems that remember: we belong to each other and to the wider world that is around us.

WHAT’S ALIVE IN YOU?

How was this piece for you? Are you resonating with the story of the first ruptures? What are you taking from this inquiry? My head is still filled with ideas and questions. So I am curious to know what is “alive in you?”

Hiraya manawari,

Lana